|

In the eyes of their Greek

contemporaries and Roman successors, the Etruscans were clearly

a different ethnic group. Dionysus from Alycarnass said, "Not

only in the language, also for the way of life and for the

costumes, the Etruscans are different from all other populations."

Etruscan society was not centralized nor dominated by a single

leader or imperial city. The towns and hilltop villages of

Etruria appear to have enjoyed considerable sovereignty. However,

they did speak the same language, shared extremely similar

religious rituals, military practices, and social customs.

Religion dominated everyday life. The Etruscans believed that

among them existed an immutable course of divine will, and

their best intellectual efforts restlessly remained devoted

to the question and interpretation of destiny. Their gods

spoke to mortals through nature and all natural events: the

flight of birds, the sound of thunder, even the strikes of

lightning bolts. The Roman Philosopher Seneca summarized the

Etruscans’ beliefs:

"Whereas we (the Romans) believe lightning to be released as

a result of the collision of the clouds, they (the Etruscans) believe

that the clouds collide so as to release lightning, for as they

attribute all to the deity, they are led to believe not that things

have a meaning in so far as they occur, but rather that they occur

because they must have a meaning."

The Etruscan obsession with religion led to a preoccupation with

the dead and the other world thus inspiring their elaborate funerary

practices. (ArtLex; UPenn; Macnamara, 152-153; Bloch, 156)

Etruscans believed that death

was the journey to the afterlife and had a fear that the neglected

dead may become malevolent; therefore, tombs were constructed

with particular care, solidity, and lavishness. Thus, the

dead would take pleasure in their last dwelling, enjoy their

afterlife, and chose not to haunt the living. The Etruscans

were fond of decorating their sarcophagi with sculptures of

humans in natural poses. In particular, the Sarcophagus

of the Spouses depicts a couple lounging on a dining

couch. It is uncertain if it actually contained the joint

remains, but it idealizes the epitome of nuptial bliss. The

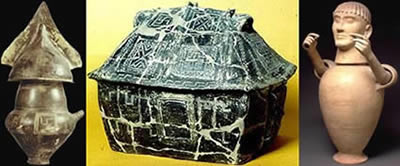

practice of cremation was quite common and decorative cinerary

or burial urns were often used to store remains. The styles

of urn range from biconical (vase shaped), to miniature hut

style to the canopic style with human figures or heads on

their lids. The sarcophagi and urns would be laid in the tomb

with other burial items necessary for the afterlife. (Adams,

198; Bloch, 157; Spivey, 92)

Biconical Urn ~ Hut Shapped Urn ~ Canopic Style Urn

Many tombs resembled houses and contained

furnishings and decorations, both real and reproduced in miniature.

The nearly intact Regolini-Galassi Tomb, discovered in

the necropolis of Etruria in 1837, is the most complete archeological

find from the "orientalizing" period of the Etruscan civilization

(late eighth to early sixth century B.C.). The tomb included jewelry,

pottery, a chariot, a nobleman's throne, and many other bronze and

gold artifacts. Sometimes the walls of tombs were frescoed with

scenes from daily life or the most important or enjoyable moments

in the deceased's life. The fresco from the Tomb of the Triclinium

shows banqueters reclining on couches while being entertained by

musicians and waited on by servants. Also depicted are many figures

of dancers and musicians playing together and a prowling Etruscan

cat on the hunt for morsels of food. Similarly, the Tomb of

the Lioness depicts themes of music, dancing and banqueting

also containing a crater that was likely used for the consumption

of wine. Both tombs’ frescoes illustrate the ubiquitous Etruscan

joie de vivre.

(ChristusRex.com; MysteriousEtruscans.com;

Spivey, 104)

|

Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Tomb of the Triclinium Fresco

Tomb of the Triclinium Fresco Detail

Tomb of the Lioness

Tomb of the Lioness Fresco Detail

You can try to take it with you...

|